You are here

The Church as Icon

People come to an Orthodox Church for a variety of reasons. Here in Washington, D.C., high school Russian language students come on field trips, university students come to fulfill a requirement for a course in Russian history or culture, Protestant and Roman Catholic seminarians come as part of their studies of other denominations, tourists come to see a bit of exotica, friends and neighbors stop by before or after tasting some of the ethnic foods sold at our bazaars, and of course, Orthodox faithful come to pray. Others come for reasons known only to themselves and to God. All are made welcome, for regardless of what prompts them to enter, that entrance may be a first step on the path to salvation.

People come to an Orthodox Church for a variety of reasons. Here in Washington, D.C., high school Russian language students come on field trips, university students come to fulfill a requirement for a course in Russian history or culture, Protestant and Roman Catholic seminarians come as part of their studies of other denominations, tourists come to see a bit of exotica, friends and neighbors stop by before or after tasting some of the ethnic foods sold at our bazaars, and of course, Orthodox faithful come to pray. Others come for reasons known only to themselves and to God. All are made welcome, for regardless of what prompts them to enter, that entrance may be a first step on the path to salvation.

One of the fundamental truths of the Christian Faith is that we are all children of God, created in His image and after His likeness. We are called to be perfect, as our Father in Heaven is perfect. Yet, seeing all around us corruption, injustice, sickness, death, the vanities of our secular existence, it is difficult to comprehend that we may strive to become perfect; it is difficult to even recognize the image of our Creator in everyone we encounter. We live in a fallen world, in which through disobedience we have chosen to cover our God-given garment of Light with the darkness of corruption, and in which we see one another through eyes dimmed by sin. The Holy Church calls us to cast off this way of seeing, to be in the world but not of the world, and to perceive and live according to our relationship to God. Our dimness of vision came over us gradually, almost imperceptibly, as mankind moved farther and farther from living after the likeness of God. The Holy Temple is a building so constructed as to gradually open our eyes to Reality, to move us toward a recognition of our relationship to our Creator, so that we might grow in His likeness.

As we make our way through this secular world, we suddenly encounter a building which stands out from its surroundings, which seems somewhat out of place. It may be shaped like the prow of a ship - reminding us of the ark in which the Holy Noah was kept safe from the flood. It may be circular - reminding us of the perfection of Creation. It may be cruciform - reminding us of the Life-giving Cross upon which the Christ died for us. It may be topped by a flat dome, or by one or many gold-leafed cupolas. We ascend the steps. Perhaps we walk around the building, examining and wondering at the painted or mosaic icons above each of doors. Whether we are believers or not, the building piques our curiosity. Standing in the courtyard before the entrance, we wonder whether to enter and satisfy that curiosity.

We know that Zaccheus climbed a sycamore tree in order to see the Christ. We can only guess at his motivation. We know that he was a wealthy tax-collector, employed by the occupying Romans, and we may surmise that he was hated by the local populace. We know that he was elderly and short of stature, and we may surmise that in climbing the tree he risked becoming an object of ridicule. Clearly he was seeking something of importance, but what - a healer, a teacher, a worker of miracles, the Messiah - we do not know. Yet as Zaccheus was waiting in the tree, Jesus stopped, and addressing him by name, invited Zaccheus to prepare to receive Him into his home. Suddenly, the Christ was no longer an object, someone to be looked upon, but someone familiar, someone with whom Zaccheus had a personal relationship. As he became aware of this relationship, he suddenly realized how far he had strayed from his responsibilities as a child of God, and publicly, he confessed his readiness to step onto the right path.

Each of us comes to the entrance of the Temple seeking something. Yet, when we finally decide to open the door and walk in, we often find something more than we had hoped to see. We enter the Narthex, a threshold from which we see the nave, filled with icons, and beyond it, elevated by several steps, a large iconostasis. The word most often heard from members of tour groups entering our Cathedral is a simple, hushed "Wow." While a believer entering the Temple might not pronounce that word, he would nonetheless feel something analogous in his heart. The Christ calls for Zaccheus to come down from the tree, so that He might dine in his home. For the first time, Zaccheus not only recognizes the One Whom he has been seeking, but sees that the Lord loves him and, despite Zaccheus' sinful past, wishes to become part of his life. As we stand in the narthex, we find ourselves between the fallen world and a different realm, a world bathed in a light not of the secular world. The Christ invites us to come out of the fallen world and into His heavenly kingdom. Not everyone immediately responds to that invitation. Many prefer to remain on the threshold, not sure how much will be demanded of them in that new realm, not sure how much of the old man they will be called to cast away. In earlier times, those who were not baptized and those who had separated themselves from the Body of the Church dared come no farther than the narthex.

Each of us comes to the entrance of the Temple seeking something. Yet, when we finally decide to open the door and walk in, we often find something more than we had hoped to see. We enter the Narthex, a threshold from which we see the nave, filled with icons, and beyond it, elevated by several steps, a large iconostasis. The word most often heard from members of tour groups entering our Cathedral is a simple, hushed "Wow." While a believer entering the Temple might not pronounce that word, he would nonetheless feel something analogous in his heart. The Christ calls for Zaccheus to come down from the tree, so that He might dine in his home. For the first time, Zaccheus not only recognizes the One Whom he has been seeking, but sees that the Lord loves him and, despite Zaccheus' sinful past, wishes to become part of his life. As we stand in the narthex, we find ourselves between the fallen world and a different realm, a world bathed in a light not of the secular world. The Christ invites us to come out of the fallen world and into His heavenly kingdom. Not everyone immediately responds to that invitation. Many prefer to remain on the threshold, not sure how much will be demanded of them in that new realm, not sure how much of the old man they will be called to cast away. In earlier times, those who were not baptized and those who had separated themselves from the Body of the Church dared come no farther than the narthex.

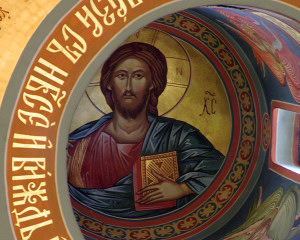

Once we enter the nave, the world of the Church is no longer before us, but instead surrounds us. We in fact become part of that world. Looking up into the central cupola, we see the Christ Pantocrator. The Ruler of all creation looks down upon it and blesses all. Below Him, within the cylinder supporting the cupola, are representations of the six-winged seraphim, angels who are in constant attendance at the Heavenly Throne. Below them, written in chain calligraphy are the words "Look down from the heavens, O Lord, upon this vine which Thou didst plant with Thy right hand, and keep it." Spread out within the chetverik, or vault, is the realm of Heaven, bathed in the golden light of Christ.

Once we enter the nave, the world of the Church is no longer before us, but instead surrounds us. We in fact become part of that world. Looking up into the central cupola, we see the Christ Pantocrator. The Ruler of all creation looks down upon it and blesses all. Below Him, within the cylinder supporting the cupola, are representations of the six-winged seraphim, angels who are in constant attendance at the Heavenly Throne. Below them, written in chain calligraphy are the words "Look down from the heavens, O Lord, upon this vine which Thou didst plant with Thy right hand, and keep it." Spread out within the chetverik, or vault, is the realm of Heaven, bathed in the golden light of Christ.  Holy Archangels, garbed in military attire stand on stylized clouds. Among them, two figures stand not upon clouds but upon platforms: To the West stands St. John the Great Prophet, Forerunner and Baptist of our Lord. To the East stands the Most Holy Theotokos. They are both human, as we are, and thus stand upon the earth. However, they link Heaven and earth - The Most Holy Theotokos by bearing God Incarnate into the world, and St. John by pronouncing the greatest message to be heard by mankind since the Fall: "This is the Lamb of God, come to take away the sins of the world!" The word "angel" means "messenger," and so St. John, announcing the coming of the long-awaited Savior, is depicted with angelic wings. In the corners of the vault are monochromatic representations of Holy Angels. While we cannot see the Holy Angels, we know they exist throughout God's creation. Monochromatic representations are a way of depicting that which is, but which cannot be seen or comprehended by the senses and intellect.

Holy Archangels, garbed in military attire stand on stylized clouds. Among them, two figures stand not upon clouds but upon platforms: To the West stands St. John the Great Prophet, Forerunner and Baptist of our Lord. To the East stands the Most Holy Theotokos. They are both human, as we are, and thus stand upon the earth. However, they link Heaven and earth - The Most Holy Theotokos by bearing God Incarnate into the world, and St. John by pronouncing the greatest message to be heard by mankind since the Fall: "This is the Lamb of God, come to take away the sins of the world!" The word "angel" means "messenger," and so St. John, announcing the coming of the long-awaited Savior, is depicted with angelic wings. In the corners of the vault are monochromatic representations of Holy Angels. While we cannot see the Holy Angels, we know they exist throughout God's creation. Monochromatic representations are a way of depicting that which is, but which cannot be seen or comprehended by the senses and intellect.

Below the vault of Heaven are depicted four of the Great Feasts of the Church: to the East, the Holy Ascension, to the North, the Holy Transfiguration on Mount Tabor, to the South, the Descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles at Pentecost, and to the West, the Glorious Second Coming. In the corners of the arches supporting the chetverik are the Holy Evangelists, apostles who recorded the events in the earthly life of Christ and bore witness to the Good News, or Gospel, of his Resurrection. On the Eastern arch supporting the vault is depicted the Annunciation. Acceding to God's will, the Virgin Mary accepts the awesome responsibility of bearing God within her body, of being the Theotokos. With her voluntary assent to the will of God, the promised Savior comes into the world. On the upper portion of the Southern wall, we see the story of the Nativity of our Lord. Looking across to the North, we see the result of the Incarnation. Standing upon the broken doors of death, our resurrected Lord pulls out of death our Ancestors Adam, Eve and Abel. Standing among the Holy Prophets who had waited for and pointed to this day, is St. John the Baptist, indicating to them the fulfillment of their prophecies. Scattered about the pit of death are broken locks and keys. With the Holy Resurrection, death has no more dominion. Death itself is depicted limp and powerless, being cast into the pit.

Beneath the icons of the Holy Nativity and Glorious Resurrection are scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist.

Beneath the icons of the Holy Nativity and Glorious Resurrection are scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist.

To the front of the church are banners. They remind us the Christian life is a life of struggle to achieve our salvation.

To the front of the church are banners. They remind us the Christian life is a life of struggle to achieve our salvation.

Many other icons of the saints from our history are in the church. Some are on the pillars of the church. Some are "portable icons" and some are on the walls.

We pause to consider the sum of the parts. The Creator looks down from on high and blesses His creation. The whole of creation unfolds around us: the Heavenly Throne, the vault of Heaven, and the history of mankind. The chandelier hanging above us represents that portion of the Church, which exists but which we cannot see: our ancestors who died in Christ, and the Bodiless Powers. If a bishop is serving, his cathedra stands at the center of the nave. We, who stand in the nave, surrounding our bishop, are members of the contemporary Church. Together, Christ's representative and his earthly flock form an icon which mirrors that depicted on the interior of the Temple: Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, surrounded by His Church. Gradually, we come to understand that the Temple itself is an icon of the universal Church. In grasping the pattern and structure of what surrounds us, we begin to understand the Christ's statement: "Where two or three are gathered in My Name, there I am." If he was in Moses, in Elias, in our great-grandparents, and in all of the members of the Church throughout history, and He is in us, then the entire Universal Church is with us when we worship Him.

We see that the entire Temple is an icon of mankind's relationship to its Creator, and we see that each of us is an essential part of that icon. With perception of that relationship comes recognition of our responsibility before our Creator. Zaccheus had hoped to see the Christ. With the recognition that Our Lord offered to be part of his life, Zaccheus became a different man. Before everyone, he humbled himself, and promised to return fourfold what he had misappropriated. In short, he confessed that he was ready to repent of his past misdeeds, and to live according to the commandments. Perhaps we had entered the nave only to get a better look at some art. Instead, we came to see that we were part of the image depicted within the Temple, and were presented with the opportunity to once again consider what God expects of us.

The Lord tells us, if you love Me, you will keep My commandments. He exhorts us to be perfect, as our Heavenly Father is perfect. He directs us to love one another, and to share in His Body and Blood. Reflecting on how far we have strayed from those instructions, and what must do to get on the Path toward communion with God, we turn our gaze to the East, to the Holy of Holies.

![]() Our view of the altar, the Holy of Holies, is blocked by high iconostasis, or icon screen. It is a physical reminder that we have placed barriers between God and ourselves. We have acted throughout history not according to His will, and, through our transgressions we have sullied His image. In our ever-increasing fascination with rationalism, with reducing reality to that which can be scientifically measured, tested, and defined, we have found it ever more difficult to face the illogic of central premises of our Faith: God becomes man, in order to suffer and die for the sins of mankind, to be resurrected on the third day, so that man may share in His Resurrection. Such ideas defy reason. Our intellect can become a barrier to belief, an impediment to seeing the truth of the Christian faith. Although the iconostasis represents that barrier, at the same time, it teaches us how to overcome the barrier. The top of the iconostasis is crowned with the life-giving Cross. If Christ had not died on the Cross, all that we are discussing would make no sense. At the center of the top row, is the icon of the Theotokos, presenting to us the Savior, the fulfillment of that which was promised in the Old Testament. Flanking her are the prophets who spoke of the coming incarnation.

Our view of the altar, the Holy of Holies, is blocked by high iconostasis, or icon screen. It is a physical reminder that we have placed barriers between God and ourselves. We have acted throughout history not according to His will, and, through our transgressions we have sullied His image. In our ever-increasing fascination with rationalism, with reducing reality to that which can be scientifically measured, tested, and defined, we have found it ever more difficult to face the illogic of central premises of our Faith: God becomes man, in order to suffer and die for the sins of mankind, to be resurrected on the third day, so that man may share in His Resurrection. Such ideas defy reason. Our intellect can become a barrier to belief, an impediment to seeing the truth of the Christian faith. Although the iconostasis represents that barrier, at the same time, it teaches us how to overcome the barrier. The top of the iconostasis is crowned with the life-giving Cross. If Christ had not died on the Cross, all that we are discussing would make no sense. At the center of the top row, is the icon of the Theotokos, presenting to us the Savior, the fulfillment of that which was promised in the Old Testament. Flanking her are the prophets who spoke of the coming incarnation.

The next row presents us with a chronological history of the liturgical year. Depicted are the immediate events in the life of the Theotokos and the earthly life of the Christ, which were involved in the fulfillment of the plan of our Salvation.

At the center of the next row, known as the deeis row, is a large icon of the Savior in His Glory, flanked by representatives of those who make up His Holy Church. People have seen the Christ, have walked with him, noted his appearance, and recorded his words. Therefore, He is very sharply delineated. However, the Throne is depicted as a monochromatic image, somewhat difficult to discern. We can only imagine, and that imperfectly, the Heavenly Throne. However, we have seen the throne upon which the Byzantine emperor, the anointed Christian monarch, sat. Therefore, in attempting to represent the Heavenly Throne, we draw the outline of a Byzantine throne. The icon of the Savior in His Glory is also known as the icon of the Eighth Day of Creation. To understand this concept, we must reflect on how we measure time: We can look at our time on earth as a short span, beginning with birth and ending with death, within a broad continuum of history which stretches from the beginning to some unreachable and incomprehensible infinity. We can look at it in terms of cycles: We toll 60 minutes, and a new hour begins, 24 hours, and a new day begins, 7 days and a new week begins. Almost two thousand years ago, on the 6th day of the week, the Christ ascended the Cross and died for us. The 7th day was the Sabbath. Early in the morning, on the 8th day, i.e. the 1st day of the following week, the Myrrh-bearing women came to the empty tomb, and bore witness to the Glorious Resurrection. With the Resurrection, death could no longer mark the end of life. Entering this Eighth Day, we enter into a new day, a day which has no end. The Lord completed his creation in 6 days, and rested on the 7th. The whole of history has taken place within that 7th day. The life in Christ is in that 8th day. We had been moving along a horizontal, temporal line. Suddenly, we encountered the Cross, and were drawn up out of that horizontal into life outside of time, into the life of the 8th day.

At the center of the next row, known as the deeis row, is a large icon of the Savior in His Glory, flanked by representatives of those who make up His Holy Church. People have seen the Christ, have walked with him, noted his appearance, and recorded his words. Therefore, He is very sharply delineated. However, the Throne is depicted as a monochromatic image, somewhat difficult to discern. We can only imagine, and that imperfectly, the Heavenly Throne. However, we have seen the throne upon which the Byzantine emperor, the anointed Christian monarch, sat. Therefore, in attempting to represent the Heavenly Throne, we draw the outline of a Byzantine throne. The icon of the Savior in His Glory is also known as the icon of the Eighth Day of Creation. To understand this concept, we must reflect on how we measure time: We can look at our time on earth as a short span, beginning with birth and ending with death, within a broad continuum of history which stretches from the beginning to some unreachable and incomprehensible infinity. We can look at it in terms of cycles: We toll 60 minutes, and a new hour begins, 24 hours, and a new day begins, 7 days and a new week begins. Almost two thousand years ago, on the 6th day of the week, the Christ ascended the Cross and died for us. The 7th day was the Sabbath. Early in the morning, on the 8th day, i.e. the 1st day of the following week, the Myrrh-bearing women came to the empty tomb, and bore witness to the Glorious Resurrection. With the Resurrection, death could no longer mark the end of life. Entering this Eighth Day, we enter into a new day, a day which has no end. The Lord completed his creation in 6 days, and rested on the 7th. The whole of history has taken place within that 7th day. The life in Christ is in that 8th day. We had been moving along a horizontal, temporal line. Suddenly, we encountered the Cross, and were drawn up out of that horizontal into life outside of time, into the life of the 8th day.

We turn our attention to the lower portion of the iconostasis: We notice that while within each of the upper rows, the icons are uniform in size and style, the lowest row includes icons of various sizes and styles of execution. It is as if icons acquired from various sources over a period of time have been assembled into this row. In fact, this row is called the assembled row, for it often includes an ensemble of the most venerated icons acquired by a given parish. It too has a definite pattern. In every Orthodox Church, the assembled row is pierced by three doors: the central double gate known as the Royal Doors, and two single doors know as deacons' or servers' doors. To the right of the Royal doors is an icon of Christ our Saviour, and to the left is an icon of the Theotokos.

We turn our attention to the lower portion of the iconostasis: We notice that while within each of the upper rows, the icons are uniform in size and style, the lowest row includes icons of various sizes and styles of execution. It is as if icons acquired from various sources over a period of time have been assembled into this row. In fact, this row is called the assembled row, for it often includes an ensemble of the most venerated icons acquired by a given parish. It too has a definite pattern. In every Orthodox Church, the assembled row is pierced by three doors: the central double gate known as the Royal Doors, and two single doors know as deacons' or servers' doors. To the right of the Royal doors is an icon of Christ our Saviour, and to the left is an icon of the Theotokos.

Above the right door, surrounding an icon of the promised Savior, we see the story of the man's creation, fall, and exile from paradise. On the actual door is depicted St. Michael the Archangel, guarding the gates of Paradise. Here we are reminded that it was our disobedience that caused us to live in a fallen world.

Above the Royal Doors is depicted the icon of the Holy Trinity, an icon also known as the Hospitality of Abraham. In offering hospitality to the three angels, whom he addressed as "My Lord," the Holy Patriarch Abraham encountered God. Flanking that icon, the Christ offers his Holy Precious Body and Blood to his disciples. On the left, he offers St. Peter a portion of His Body. On the right He offers St. Paul His Blood. Of course, reason states that St. Paul was not in the upper room at the time of the Last Supper. However, we have already seen that in the 8th day, we are not bound by time. In coming to believe, St. Paul became part of the Body of Christ. In partaking of Holy Communion, he like all communicants before and since, entered into that upper room, and received the Body and Blood of Christ from Christ Himself. The idea that we are called to step outside of time, in order to enter into the upper room and commune with God, is often a stumbling block to those who have rejected the Tradition of the Holy Church. Where in the Holy Bible is this illogical teaching that we step outside of time? Perhaps we should turn to the Gospel account of the Holy Transfiguration, and then look at the icon on the North wall of the Temple. The Christ ascends Mt. Tabor, and shows Himself in His Glory to three disciples. At the same time, he speaks with two individuals whom St. Peter recognizes as the Holy Prophets Moses and Elias [Elijah]. From the Bible, we know that Moses died and was buried in Sinai. We also know that Elias went up into Heaven in the fiery chariot. Yet God speaks with them and with His disciples, together, outside of time.

Above the Royal Doors is depicted the icon of the Holy Trinity, an icon also known as the Hospitality of Abraham. In offering hospitality to the three angels, whom he addressed as "My Lord," the Holy Patriarch Abraham encountered God. Flanking that icon, the Christ offers his Holy Precious Body and Blood to his disciples. On the left, he offers St. Peter a portion of His Body. On the right He offers St. Paul His Blood. Of course, reason states that St. Paul was not in the upper room at the time of the Last Supper. However, we have already seen that in the 8th day, we are not bound by time. In coming to believe, St. Paul became part of the Body of Christ. In partaking of Holy Communion, he like all communicants before and since, entered into that upper room, and received the Body and Blood of Christ from Christ Himself. The idea that we are called to step outside of time, in order to enter into the upper room and commune with God, is often a stumbling block to those who have rejected the Tradition of the Holy Church. Where in the Holy Bible is this illogical teaching that we step outside of time? Perhaps we should turn to the Gospel account of the Holy Transfiguration, and then look at the icon on the North wall of the Temple. The Christ ascends Mt. Tabor, and shows Himself in His Glory to three disciples. At the same time, he speaks with two individuals whom St. Peter recognizes as the Holy Prophets Moses and Elias [Elijah]. From the Bible, we know that Moses died and was buried in Sinai. We also know that Elias went up into Heaven in the fiery chariot. Yet God speaks with them and with His disciples, together, outside of time.

We return to the iconostasis. The Royal Doors represent the entrance into Paradise. Behind them is a curtain, representing both the veil of the Temple and the rock, which was rolled away from the door of the tomb. On the Royal Doors is an icon of the Annunciation. With the voluntary assent of the Virgin Mary to the will of God, the immediate process of our salvation, of the opening of the doors to paradise, was begun. Had the story of the Incarnation not been passed on to us, we would still be waiting, bound by death. Therefore, below the icon of the Annunciation are icons of the Holy Evangelists, those who recorded the Good News for the world. Not everyone can read. However, even one who is unlettered can take part in the Divine Liturgy, the eucharistic service at which is distributed the precious Body and Blood of Christ. Therefore, we see flanking the Holy Evangelists, icons of the liturgists Sts. Basil the Great, John Chrysostomos, Gregory the Dialogist, and James the Brother of Our Lord, composers of our eucharistic services. Depicted are those who helped spread the faith. Also depicted are deacons, who take part in preparing the people for the coming of Christ, and who invite them to partake of the Precious Body and Blood of Christ.

The upper rows of the iconostasis had shown us our history, the events through which our salvation was effected, and the Heavenly Throne to which we are all called. The Royal Doors revealed to us the entrance into Paradise, and the Southern deacon's door showed us what has kept us from entering into Paradise. The icon on the Northern door teaches us how to enter. Two thieves were crucified with the Christ. One chose to revile him. The other, the Wise Thief, instead confessed the Christ, and asked that the Christ remember him in His Kingdom. The Christ responded with the words, "This very day you will be with me in Paradise." We enter Paradise not as the result of our manner of dress, our good works, or the rule of prayer, which we follow; these are all consequences of what has happened in our hearts. The depiction of the Wise Thief on the Northern door reminds us that we must first of all confess our faith in the Lord, and accept what God has done for us and for our salvation. We must recognize our unworthiness before God, and ask for His mercy. If we maintain that attitude of repentance, if we humbly live according to our Faith, the rest will follow, and we will become heirs to the Kingdom of God. An icon above the Northern door depicts the holy Patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Within the folds of their robes are many faces. In emulating the witness and repentance shown by the Wise Thief, we too become children of Abraham by adoption, we too rest in the bosom of Abraham.

The upper rows of the iconostasis had shown us our history, the events through which our salvation was effected, and the Heavenly Throne to which we are all called. The Royal Doors revealed to us the entrance into Paradise, and the Southern deacon's door showed us what has kept us from entering into Paradise. The icon on the Northern door teaches us how to enter. Two thieves were crucified with the Christ. One chose to revile him. The other, the Wise Thief, instead confessed the Christ, and asked that the Christ remember him in His Kingdom. The Christ responded with the words, "This very day you will be with me in Paradise." We enter Paradise not as the result of our manner of dress, our good works, or the rule of prayer, which we follow; these are all consequences of what has happened in our hearts. The depiction of the Wise Thief on the Northern door reminds us that we must first of all confess our faith in the Lord, and accept what God has done for us and for our salvation. We must recognize our unworthiness before God, and ask for His mercy. If we maintain that attitude of repentance, if we humbly live according to our Faith, the rest will follow, and we will become heirs to the Kingdom of God. An icon above the Northern door depicts the holy Patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Within the folds of their robes are many faces. In emulating the witness and repentance shown by the Wise Thief, we too become children of Abraham by adoption, we too rest in the bosom of Abraham.

Having received so much more than we had expected to find within these walls, we turn to leave. Even here, the Temple teaches us an important lesson. On the Western wall, we see the Glorious Second Coming, we see the 12 apostles judging the 12 tribes, we see the scales of the Dread Judgment, we see the souls of the righteous resting in the right hand of God, and we see our clear choice - to enter with the righteous into the Kingdom of Heaven, or to consign ourselves to the sufferings in hell. The choice is ours. The Western wall reminds us that while we may leave the Temple, both the joys and responsibilities laid out for us here remain with us. Ultimately, we will each face our Creator, and will be called to account for what we have done here on earth.

As an awareness of the Divine pattern grows in us, we begin to look upon each individual part in a different light. We see ourselves as part of the family, which surrounds us, a family composed of many different types of people with different gifts, each an example of how to live the life in Christ. As we marvel at this variety, we are struck with what is for many art students another stumbling block. The faces of so many of the icons are identical to one another, and almost without exception, they transmit a feeling of quiet joy. This does not reflect laziness on the part of the iconographer. His purpose is not to depict secular reality. Rather, he is called to depict reality in the light of the Holy Transfiguration, to depict not simply a human face, but the Image of the Creator which is in all of us. In other essays on this page, we will explore the language of iconography.

As an awareness of the Divine pattern grows in us, we begin to look upon each individual part in a different light. We see ourselves as part of the family, which surrounds us, a family composed of many different types of people with different gifts, each an example of how to live the life in Christ. As we marvel at this variety, we are struck with what is for many art students another stumbling block. The faces of so many of the icons are identical to one another, and almost without exception, they transmit a feeling of quiet joy. This does not reflect laziness on the part of the iconographer. His purpose is not to depict secular reality. Rather, he is called to depict reality in the light of the Holy Transfiguration, to depict not simply a human face, but the Image of the Creator which is in all of us. In other essays on this page, we will explore the language of iconography.

Unfortunately, our words are not sufficient to teach the lessons to be found in that Icon which is the Holy Temple. We present a simple invitation, repeated by many who have wanted to share the Joy of the Resurrection: "Come and see!"

PARISH LIFE

RECENT VIDEOS

Address of our Cathedral

Subscribe to our mailing list

While all the materials on this site are copyrighted, you may use them freely as long as you treat them

with respect and provide attribution on the Russian Orthodox Cathedral of St.John the Baptist of Washington DC.